Jun 17 2020

With countries easing up on lockdown restrictions, COVID-19 is altering the way individuals use indoor spaces. However, that poses a challenge to people who handle those spaces, right from homes to factories and offices.

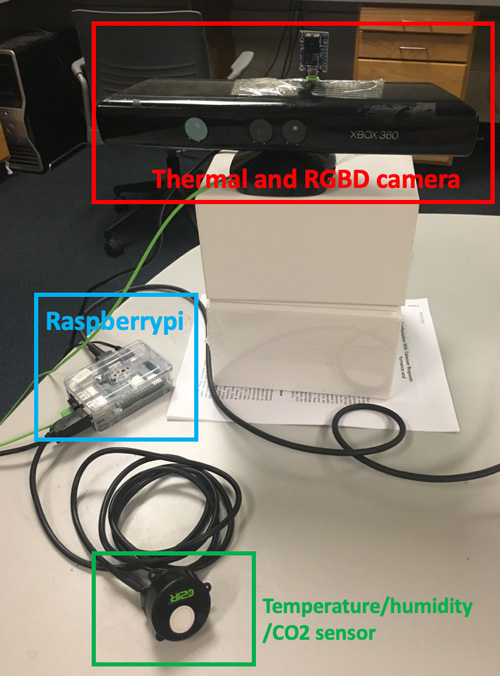

A closer look at the HEAT prototype. Image Credit: University of Michigan.

A closer look at the HEAT prototype. Image Credit: University of Michigan.

Heating and cooling is one of the top challenges and is estimated to be the largest consumer of energy in commercial buildings and homes in the United States. Smarter and more flexible climate control is required to keep people comfortable and without the need for heating and cooling the entire vacant buildings.

The University of Michigan researchers have now come up with a novel solution that may offer more efficient and more personalized comfort, and fully eliminate the wall-mounted thermostats that people are accustomed to.

A study, published in the July 2020 issue of Building and Environment, has described Human Embodied Autonomous Thermostat, or “HEAT,” for short. This system combines three-dimensional (3D) video cameras and thermal cameras to quantify whether the occupants of the building are feeling hot or cold by monitoring their facial temperature.

The system subsequently feeds the resultant temperature data to a predictive model, which, in turn, compares it with the data about the thermal preferences of the occupants. Finally, it establishes the temperature that will ensure the comfort of the largest number of building occupants with the least energy expenditure.

The latest study demonstrates how the system is able to sustain the comfort of 10 building occupants in a laboratory environment, in an effective and efficient way.

COVID presents a variety of new climate control challenges, as buildings are occupied less consistently and people struggle to stay comfortable while wearing masks and other protective gear.

Carol Menassa, Study Co-Author and Associate Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Michigan

Menassa continued, “HEAT could provide an unobtrusive way to maximize comfort while using less energy. The key innovation here is that we’re able to measure comfort without requiring users to wear any detection devices and without the need for a separate camera for each occupant.”

Menassa is also the principal investigator of the project.

HEAT operates somewhat similar to present-day internet-enabled learning thermostats. When the system is newly set up, occupants will usually teach it about their preferences by occasionally sending it feedback from their smartphones on a three-point scale: “comfortable,” “too cold,” or “too hot.” After some days, HEAT learns the occupants’ preferences and works on its own.

The scientists are currently working with Southern Power—a power company—to start testing HEAT in their Alabama offices, where the corners of the rooms will be installed with test cameras fixed on tripods. Cameras would be positioned less conspicuously in a permanent installation, explained Menassa.

These cameras gather temperature data without detecting people, and all the captured footage is deleted instantly after processing, often in less than a few seconds.

Another test, also performed in association with Southern Power, will position the system in an Alabama community of recently built smart homes. The researchers believe that a residential system would soon be available in the market in less than five years.

Menassa added that facial temperature is an excellent predictor of comfort. When individuals feel hot, their blood vessels widen to radiate the extra heat, increasing the facial temperature. Similarly, when they feel too cold, the blood vessels constrict, cooling the face temperature.

Although previous iterations of the system also made use of body temperature to predict the comfort level, they needed users to wear wristbands that directly determined the body temperature, and to offer constant feedback regarding their comfort level.

The cameras we’re using are common and inexpensive, and the model works very well in a residential context. Internet-enabled thermostats that detect you and learn from you have sort of built a platform for the next phase, where there’s no visible thermostat at all.

Vineet Kamat, Study Co-Author and Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, and Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of Michigan

The predictive model of HEAT was developed by industrial operations and engineering associate professor Eunshin Byon from the University of Michigan. Byon is also the study’s author. According to her, tweaking the model could render the system useful in applications beyond offices and homes—for instance, in hospitals where care providers find it hard to remain comfortable under masks and other similar protective equipment.

The COVID-19 pandemic requires nurses and other hospital workers to wear a lot of protective gear, and they’ve struggled to stay comfortable in the fast-faced hospital environment. The HEAT system could be adapted to help them stay comfortable by adjusting room temperature or even by signaling to them when they need to take a break.

Eunshin Byon, Study Author and Associate Professor, Industrial Operations and Engineering, University of Michigan

In association with the University of Michigan’s school of nursing, Menassa’s research team has already performed a pilot study that investigated how the system can be effectively employed to offer personalized thermal comfort for nurses operating in healthcare settings such as chemotherapy administration units.

HEAT is now available as a licensable technology via the Office of Technology Transfer at the University of Michigan. The study was funded by the National Science Foundation, grant numbers CBET 1804321 and CBET 1349921.

The scientists, who have filed patent applications relevant to the technology, also includes former graduate research assistant Da Li from the University of Michigan, who is currently an assistant professor of civil engineering at Clemson University.

Optimizing comfort for nurses in high-stress situations with sensors

Video Credit: University of Michigan.

Journal Reference:

Li, D., et al. (2020) HEAT - Human Embodied Autonomous Thermostat. Building and Environment. doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106879.