Jul 6 2017

The concept of green-infrastructure is quite attractive, but there is apprehension regarding its effectiveness. Researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign are employing a mathematical approach traditionally used in earthquake engineering to establish how well green- infrastructure functions, and to communicate with Policymakers, Urban Planners and Developers.

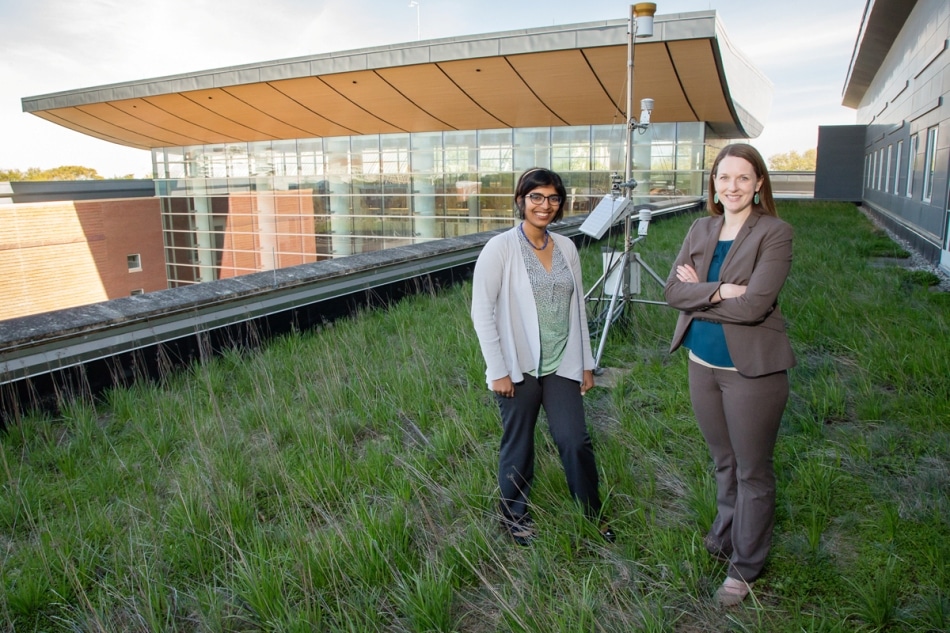

Graduate student Reshmina William, left, and civil and environmental engineering professor Ashlynn Stillwell pause on the green roof over the Business Instructional Facility at the University of Illinois. Their research is helping to simultaneously evaluate the performance of green roofs and communicate their findings with urban planners, policymakers and the general public. (Photo by L. Brian Stauffer)

Graduate student Reshmina William, left, and civil and environmental engineering professor Ashlynn Stillwell pause on the green roof over the Business Instructional Facility at the University of Illinois. Their research is helping to simultaneously evaluate the performance of green roofs and communicate their findings with urban planners, policymakers and the general public. (Photo by L. Brian Stauffer)

Green roofs are flat, vegetated surfaces on the tops of buildings that are engineered to catch and retain rainwater and filter any that is discharged back into the environment.

“The retention helps ease the strain that large amounts of rain put on municipal sewer systems, and filtration helps remove any possible contaminants found in the stormwater,” said Reshmina William, a Civil and Environmental Engineering Graduate Student who conducted the research with Civil and Environmental Engineering Professor Ashlynn Stillwell.

A good-for-the-environment solution to moderating stormwater overflow may look like a no-brainer, but a general concern regarding green roofs is the unpredictability of their performance. One challenge is discovering how well the buildings that hold them up will react to the added and highly variable weight between dry and wet conditions. William expressed that another challenge is establishing how well the roofs retain and process water given storms of different duration, intensity, and frequency.

While exploring reliability analysis in one of her courses, William thought of the idea to use an apparently unconnected mathematical concept called fragility curves to defy this problem.

Earthquake engineering has a similar problem because it is tough to predict what an earthquake is going to do to a building. Green infrastructure has a lot more variability, but that is what makes fragility curves ideal for capturing and defining the sort of dynamics involved.

Reshmina William, a Civil and Environmental Engineering Graduate Student

William and Stillwell chose to explore green roofs over other types of green infrastructure simply because there was one on campus, and it was fitted with the instrumentation required to measure soil moisture, humidity, temperature, rainfall amount and a number of other variables that are plugged into their fragility curve model.

“This is a unique situation because most green roofs don’t have monitoring equipment, so it is difficult for Scientists to study what is going on,” Stillwell said. “We are very fortunate in that respect.”

William said the main goal of this research is to enable communication between Scientists, Developers, Policymakers, and the general public about the financial risk and environmental advantage of taking on such an expense.

One of the biggest barriers to the acceptance of green infrastructures is the perception of financial risk. People want to know if the benefit of a green roof is going to justify the cost, but that risk is mitigated by knowing when an installation will be most effective, and that is where our model comes in.

Reshmina William, a Civil and Environmental Engineering Graduate Student

The results of their model and risk analysis, which have been published in the Journal of Sustainable Water in the Built Environment, provide an idea of green infrastructure performance for this specific green roof. The results from one model do not yield a one-size-fits-all approach to green infrastructure assessment, and William and Stillwell said that is one of the plus points of their method. Adaptability across varied environments and technologies is vital to any green infrastructure analysis.

This work was supported by the University of Illinois Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the Ravindar K. and Kavita Kinra Fellowship in Civil and Environmental Engineering.