Jan 4 2017

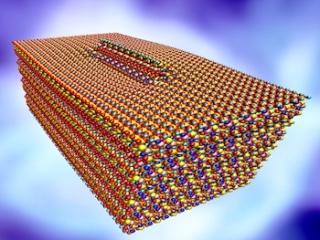

A screw dislocation disrupts the regular rows of atoms in tobermorite, naturally occurring crystalline analog to the calcium-silicate-hydrate that makes up cement. Rice University scientists simulated tobermorite to see how it uses dislocations to relieve stress when used in concrete. Courtesy of the Multiscale Materials Laboratory

A screw dislocation disrupts the regular rows of atoms in tobermorite, naturally occurring crystalline analog to the calcium-silicate-hydrate that makes up cement. Rice University scientists simulated tobermorite to see how it uses dislocations to relieve stress when used in concrete. Courtesy of the Multiscale Materials Laboratory

Although concrete is not regarded as a plastic, plasticity at small scales can boost the utility of concrete as the most-used material in the world by allowing it to continually adapt to stress, decades and sometimes even centuries post hardening. Researchers from Rice University have moved one step closer to understanding the reason for this.

Rouzbeh Shahsavari, a materials scientist at Rice University, carried out an atom-level computer analysis of tobermorite, a crystalline analog of the calcium-silicate-hydrate (C-S-H) that makes up cement, which holds concrete together. By studying tobermorite’s internal structure, researchers hope to make strong, tough and better concrete that will not crack under stress.

Their study results are published this week in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces.

Tobermorite is a key component in the superior concrete used by Romans in ancient times. It forms in layers, like paper stacks that harden into particles. These particles posses screw dislocations, or shear defects that allow the layers to slide past each other in response to stress. They can also the layers to slip until the jagged defects catch and lock them into place.

The researchers developed the first computer models of tobermorite “super cells” with dislocations either in parallel or in perpendicular with layers in the material, and then used shear force. They observed that defect-free tobermorite deformed easily when water molecules caught in between layers helped them slide past each other.

However, in particles with screw defects, the layers only slid before being caught and locked into place by the tooth-like core dislocations. This passed the buck effectively to the next layer, which glided until caught, and relieved the stress without cracking.

According Shahsavari, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering and materials science and nanoengineering, this “step-wise defect-induced gliding” around the core of the particle make it more ductile and can able to adjust to stress.

The insight we get from this study is that unlike the common intuition that defects are detrimental for materials, when it comes to complex layered crystalline systems such as tobermorite, this is not the case. Rather, the defects can lead to dislocation jogs in certain orientations, which acts as a bottleneck for gliding, thus increasing the yield stress and toughness. These latter properties are key to design concrete materials, which are concurrently strong and tough, two engineering features that are highly desired in several applications. Our study provides the first report on how to leverage seemingly weak attributes — the defects — in cement and turn them to highly desired properties, high strength and toughness

Rouzbeh Shahsavari, Materials Sciensitst, Rice University

Shahsavari said that the study will provide design guidelines for development of tougher, stronger concrete and other complex materials.

Ning Zhang, a Rice postdoctoral researcher, is lead author of the paper and Philippe Carrez, a professor at the Lille University of Science and Technology, Villeneuve d’Ascq, France, is a co-author.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) supported the research. Computing resources were supplied by the National Institutes of Health and an IBM Shared University Research award in collaboration with CISCO, Qlogic and Adaptive Computing, as well as Rice’s NSF-supported DAVinCI supercomputer administered by Rice’s Center for Research Computing and were procured in partnership with Rice’s Ken Kennedy Institute for Information Technology.